Allowing Affordable Care Act enhanced premium tax credits to expire at the end of this year would slash $32.1 billion of 2026 revenue from healthcare providers, with a $7.7 billion increase in uncompensated care demand, according to the latest analysis on the highly watched policy issue.

The Urban Institute estimate was published Thursday by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which provided funding support for the think tank’s work.

It incorporates new policies expected to be in place next year due to the summer’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) and builds on a prior projection that the premium tax credits’ expiration would lead to 7.3 million fewer people receiving subsidized coverage and 4.8 million adults becoming uninsured.

“Because lower spending on healthcare services means lower revenue for healthcare providers and fewer services rendered, the resulting decline in revenue could have adverse consequences, particularly for already financially at-risk hospitals and the communities they serve,” the report’s authors wrote in their report.

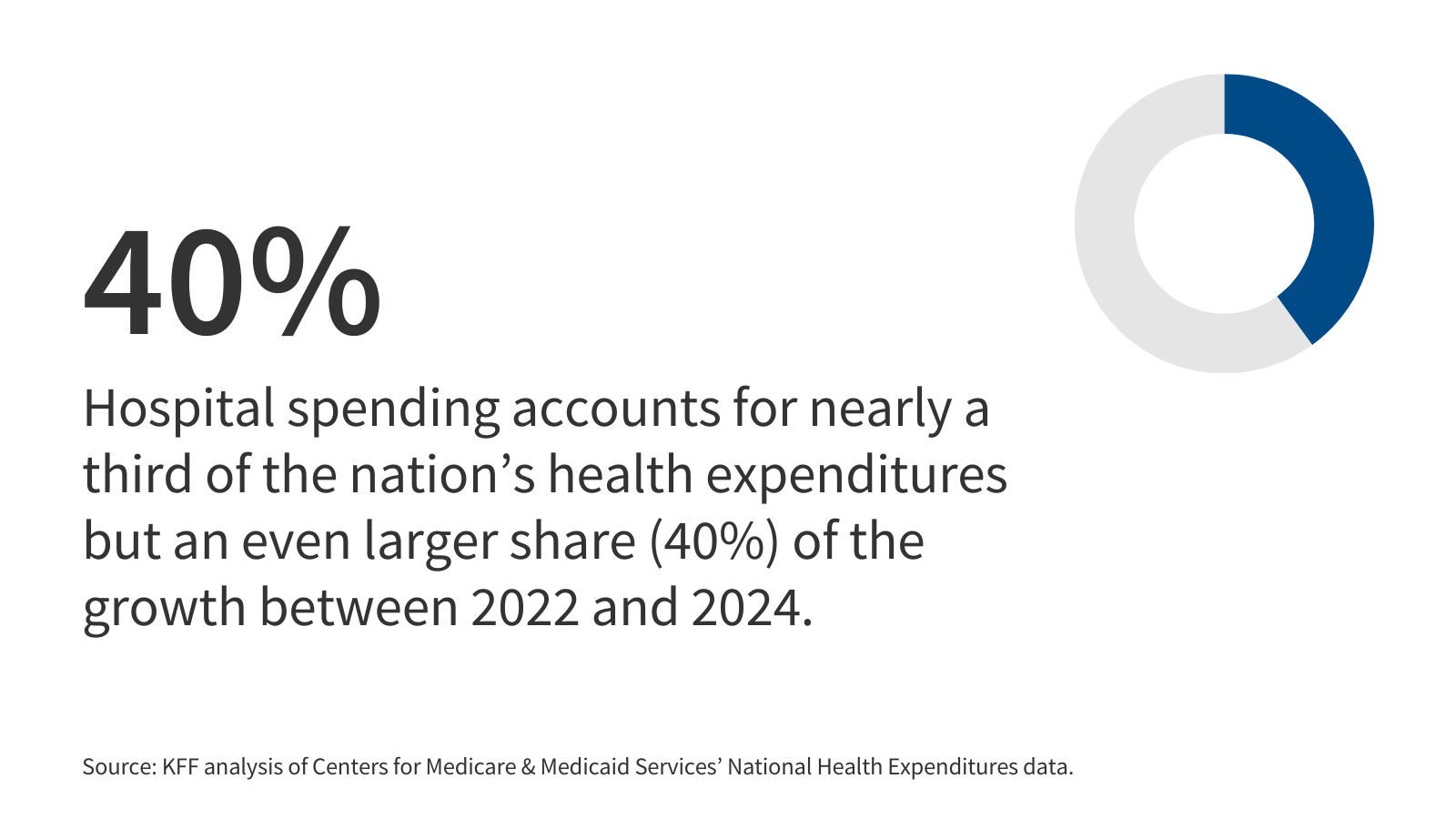

The full $32.1 billion tally represents a roughly 1.3% reduction on current total healthcare spending on nonelderly individuals, according to the report. It reflects changes in care-seeking behavior stemming from coverage changes—mainly, reduced utilization and subsequent decreases in payments by private insurers for healthcare claims as well as direct out-of-pocket spending.

More specifically, about $14.2 billion of the total reflects lowered spending on services provided by hospitals, $5.1 billion of reduced spending on services provided by office-based physicians, $5.8 billion less spent on prescription drugs and $6.9 billion less on other healthcare services (e.g., home healthcare or medical equipment).

Researchers also outlined an increase in uncompensated care sought by those newly uninsured. Within the $7.7 billion estimated total for 2026—which is an 11.6% increase over baseline should the subsidy be extended at current levels—$2.2 billion of demand would land on hospitals, $1 billion on office-based physicians, $1.5 billion tied to uncompensated prescription drug spending and $3.1 billion on other care services.

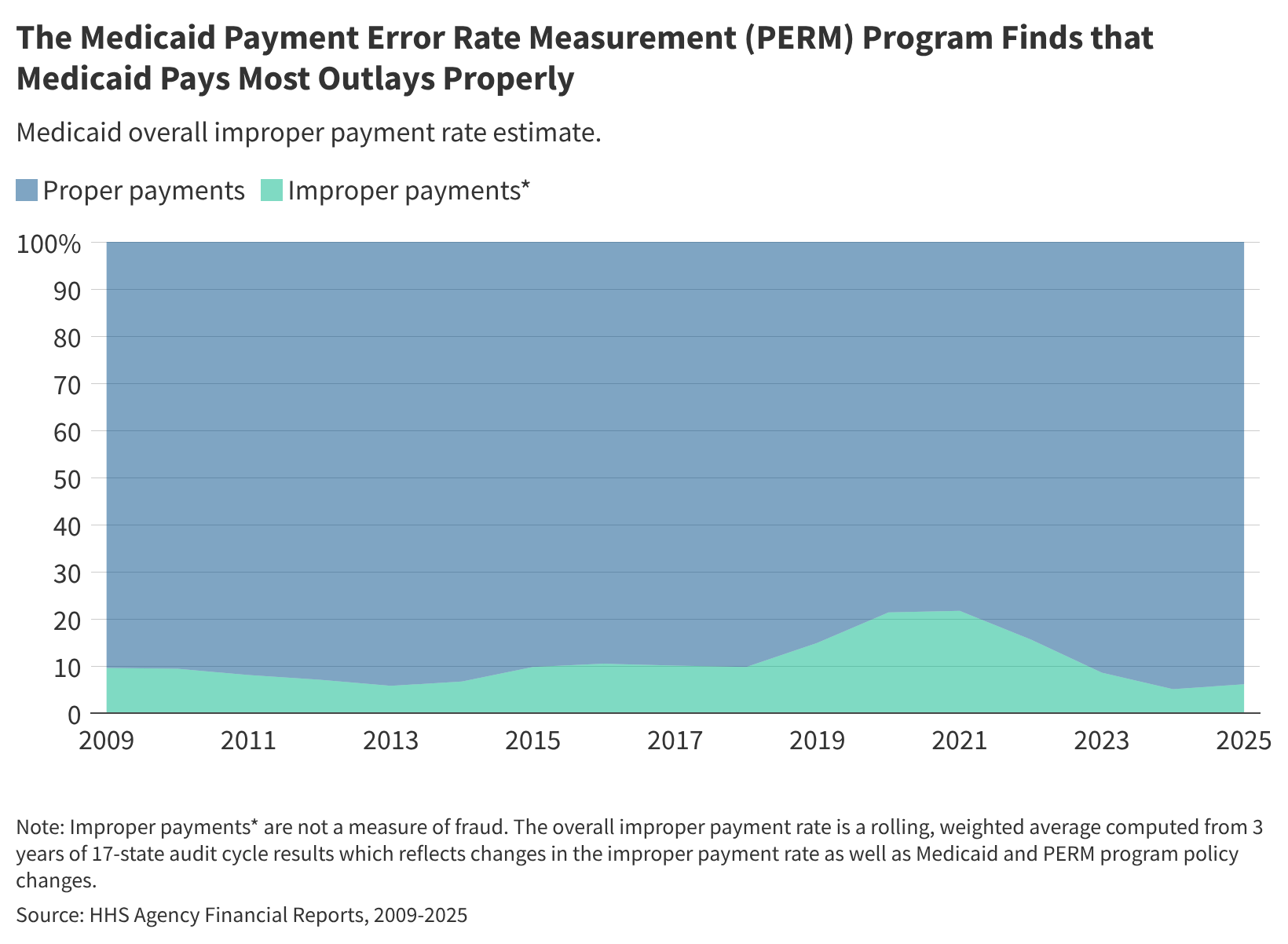

“Our estimates indicate that slightly more than half of the increase in uncompensated care would be financed by providers, 30% by the federal government, and 19% by state and local governments,” the Urban Institute researchers wrote in their report. “If government uncompensated care funding is less than we estimate, providers would be responsible for more uncompensated care, and the uninsured would forgo additional healthcare.”

The distribution of the increased demand and reduced spending would vary substantially from state to state.

The researchers estimated 14 states would have total spending declines exceeding 1% of total spending, with Southern states like Florida, Georgia and Texas all leading the way with an estimated 4.8% decline. Ten of the 11 states that would face the highest relative declines in spending are Medicaid nonexpansion states, the researchers added, which generally have larger rural populations.

Projected demand for uncompensated care would, again, cluster around nonexpansion states, which would represent nine of the 15 most heavily impacted states. The largest increases would hit Tennessee (29.2% increase), Mississippi (29.1%) and South Carolina (26.9% increase).

“The size and stability of the Marketplace, and the implications for providers, could be even more important after 2026, when the OBBBA provisions, such as further restrictions on [premium tax credit] eligibility for lawfully present immigrants and the elimination of automatic enrollment with [premium tax credits], will reduce Marketplace enrollment further, with or without enhanced [premium tax credits],” the researchers added.

Of note, some provisions of a final rule released in June—which eliminates certain special enrollment periods and could lead to 1.8 million or more people losing coverage—are currently stayed by a federal judge. The outcome of that litigation could bring further enrollment reductions, provider revenue reductions and increased uncompensated care demand, the researchers added.

The enhanced premium tax credits were adopted in 2021 amid the COVID-19 emergency and have been largely credited for boosting marketplace enrollment. Congress previously elected to extend the subsidies that now face a Dec. 31 cliff.

The issue has become a sticking point in this month’s spending bill negotiations, with Democrats refusing to sign onto a Republican-backed funding extension without concessions on the enhanced premiums and other healthcare coverage and funding items that had been clipped in the OBBBA. Republican leaders have suggested they could be open to extending the enhanced premiums but said the issue should be addressed closer to their expiration.

As of Friday, no deal has emerged between the parties with a government shutdown set to begin Oct. 1.

An extension of the enhanced premiums is largely supported by healthcare industry groups representing providers and payers alike. Those groups, as well as Democrats, have pointed to analyses suggesting premium spikes for enrollees and that coverage losses would mount with no extension or if that extension comes later than this month.

Publisher: Source link