This brief was updated on August 8, 2025 to correct the number of states that allow and prohibit minors to consent to their own contraceptive care.

Across the country, minors’ ability to consent to their health care, particularly their reproductive health care, varies significantly. Expanding “parental rights’ in health and education has been a priority for politically conservative groups and was outlined as a “top-tier” right by the Heritage Foundation in Project 2025. While parental involvement in health care can facilitate access and improve outcomes, it is not always possible for teens to include parents in decisions about sensitive health care decisions. Some teens, particularly those who have unstable home lives, are in foster care, or fear abuse if their parents were to become aware they are seeking this type of care could be more likely to experience challenges in accessing services in states where parental notification or consent is required. Beyond parental involvement, minors face additional challenges accessing transportation, scheduling appointments outside school hours, and paying for the care. This brief examines state consent requirements for minors accessing contraceptive and abortion care, processes for minors to attempt to obtain abortion without parental involvement, and trends in state policy increasing requirements for parental involvement in minors’ health care decisions.

Contraception

In 23 states and D.C. all minors, regardless of age, may consent to their own contraceptive care (Figure 1). In five other states—Alabama, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and South Carolina—minors of certain ages can consent to this type of care. Two states, Illinois and Wyoming, allow minors to consent to their own contraceptive care if they have a referral. In Wyoming minors need a referral from the Department of Health, and in Illinois minors need a referral from a clinic, such as Planned Parenthood. State laws require minors to obtain parental consent to access contraceptive services in 18 states, with the exception of over-the-counter (OTC) contraceptive methods, such as condoms, Plan B, and Opill—though the latter two may be too costly for many minors to purchase on their own. In addition, in some retail outlets, Plan B and Opill are placed behind the pharmacy counter or in locked cabinets, requiring the pharmacy staff to hand the pills to the consumer despite the fact that no prescription is required. Two states, Ohio and North Dakota, do not have any explicit laws allowing or prohibiting minors to consent to contraceptive services.

Historically, clinics that receive funds through the federal Title X family planning program have been required to offer confidential care which effectively bars participating providers from requiring parental consent for minors accessing care at their sites. This policy has applied to all Title X funded sites, regardless of whether parental consent is required in the state. This rule was challenged in a Texas case and in December 2022, a U.S. District Court in Texas ruled that this provision of the Title X regulations violates the constitutional rights of Texas parents to direct the upbringing of their children. Teens in Texas now must obtain parental consent to receive reproductive health care in Title X clinics in the state along with other sites. Minors in all other states are still entitled to confidential care and can still receive contraceptive care at Title X sites without parental consent, regardless of state law.

While many minors have coverage for contraceptive services under their parent’s health insurance plan, confidentiality is limited. The insurance company sends the Explanation of Benefits (EOB) summary of health care services used to the primary policyholder, typically the parent for a minor. While some states have implemented broad laws to ensure confidentiality when requested by minors seeking sensitive services, these laws are limited and do not apply to self-insured plans.

Abortion

Parental Involvement Laws

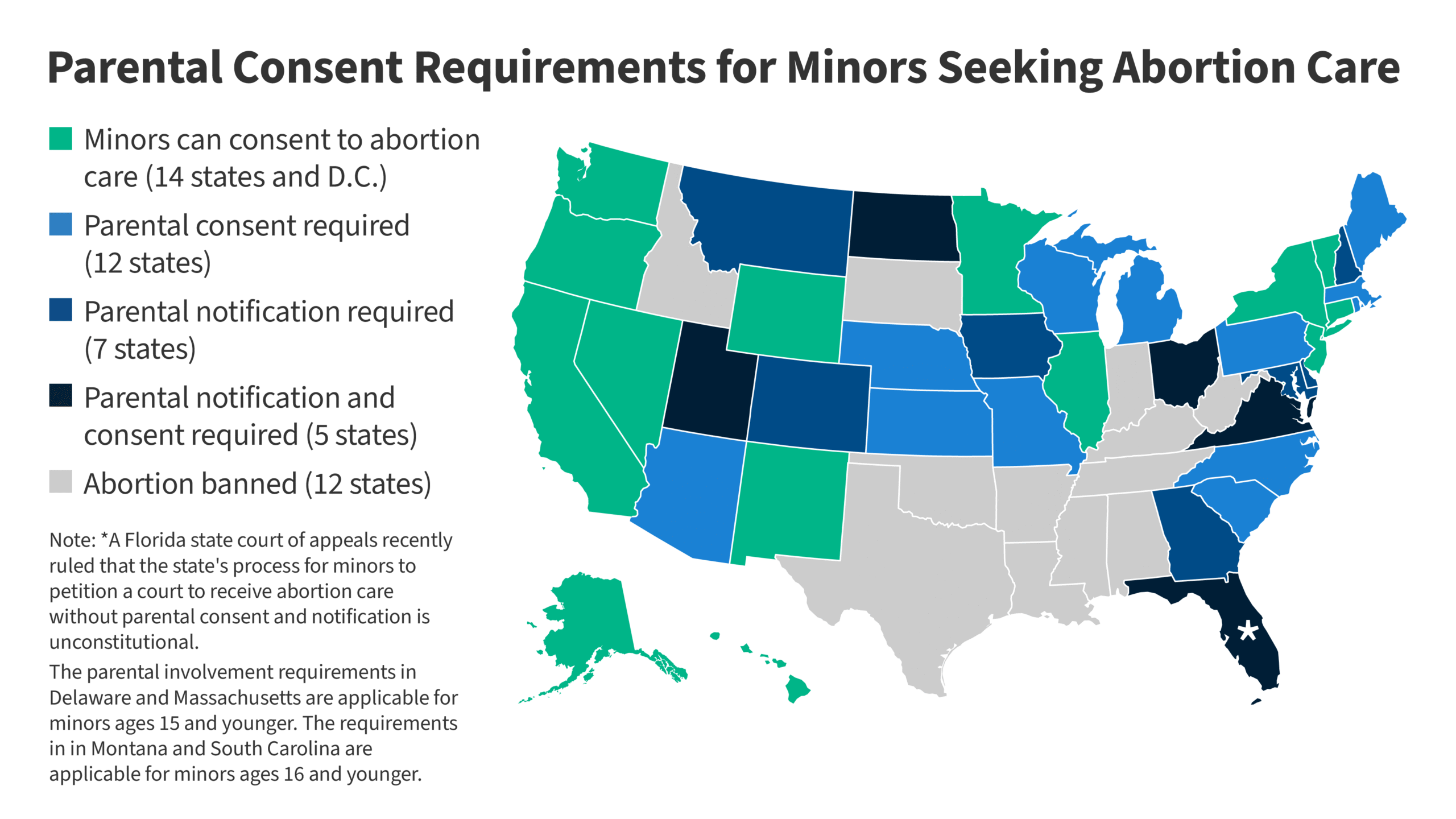

Among the states without abortion bans, 24 require some level of parental involvement in a minor’s ability to access abortion care while 14 states and D.C. have no parental involvement requirements (Figure 2). However, in one of these states, Nevada, a federal district court recently ruled that a decades-old permanent injunction blocking enforcement of the parental involvement law can go back into effect. The district court blocked enforcement of this law as an appeal makes its way through the courts, but this requirement may go back into effect soon.

State parental involvement laws generally require parental notification of a minor’s intent to receive abortion care or require parental consent for the abortion, or both notification and consent. Notification requirements vary, but they usually involve the provider informing the parent in person, by phone, or by mail with registered delivery that the minor is seeking abortion care 24-48 hours ahead of the minor actually receiving such care. When the law is limited to only parental notification, clinicians are not prohibited from providing minors with abortion care even if their parents disagree with their decision. Consent requirements generally involve the parent signing a document stating that they consent to the minor receiving an abortion. When both parental notification and consent are required, clinicians usually have to inform the parent of the minor’s intent to receive an abortion and, prior to actually providing that care, receive the signed parental consent.

Of the states without abortion bans, 12 require parental notification, 17 require parental consent, and 5 of these states require both notification of a minor’s intent to receive an abortion and parental consent to the abortion care. These requirements often impose barriers to access for minors seeking abortion services, especially for those who do not wish to involve their parents in their decision to seek abortion care, those who suffer from abuse, those whose parents or guardians disagree with their decision to receive an abortion and withhold their consent, or those whose parents are not present in their lives or are not easily accessible to them, as is the case for minors living in foster care. Additionally, the details of these requirements may be difficult to navigate for some minors and their parents, even if they are supportive of their decision to seek abortion care.

Some states, such as Kansas and Wisconsin, require that the parent be present in person at a counseling appointment prior to the appointment where the minor will be receiving abortion care. This raises further access difficulties for minors, since their parents may have difficulties taking time off from work or arranging childcare to be able to attend the counseling appointment.

Additionally, five states—Arizona, Florida, Kansas, Nebraska, and Virginia—require the parent’s written and signed consent be notarized. And two states—Florida and North Dakota—require parents to show a government-issued identification and/or proof of relationship to the minor, such as a birth certificate. These documentation requirements may be difficult for some minors and their parents to meet. The time and cost associated with getting the written consent notarized may delay care, as notary publics generally only work during business hours. Acquiring the correct documentation may be even more difficult for people living on low incomes who do not have access to a care or for people who no longer have access to an original birth certificate. In-person requests for a birth certificate generally can only be made in the county where the person was born and online requests may take weeks.

Three states—Kansas, Missouri, and North Dakota—require the involvement of both of the minor’s parents for abortion care. There are, however, some exceptions to this requirement. In four of these states, only the involvement of the custodial parent is required when the minor’s parents are divorced. The remaining state, Kentucky, makes an exception only for cases of domestic violence. However, these exceptions do not address situations where a minor’s parents are separated, but not divorced, or where one of the parents is not in the minor’s life, but there are no formal custodial agreements, or when one of the minor’s parents is incapacitated, incarcerated, or otherwise unreachable.

Eleven states allow other relatives or adults in the minor’s life to fulfill the parental consent requirement in some situations and with varying documentation requirements. For instance, in Wisconsin, a minor’s grandparent, aunt, uncle, or sibling who is over the age of 25 can consent to a minor’s abortion. In Virginia, any adult who is acting in loco parentis (i.e. an adult who has been taking care of a minor, even if they are not their legal guardian), may be notified and provide consent for the minor’s abortion. Other states, such as Nebraska, only allow other relatives to consent to the minor’s abortion if the minor attests in writing that they are abused by their parents and the physician reports this abuse to the relevant authorities.

In three of the states that have parental involvement requirements—Delaware, Maine, and Maryland—the requirement may be waived through counseling. In Delaware, mental health professionals are able to fulfill the notification requirement by providing the minor with options counseling. Maryland providers are able to waive the requirement themselves by determining that the minor is mature and capable of giving informed consent or if notification would not be in the best interest of the minor. And in Maine, the consent of a counselor can stand in place of the consent of a parent. Physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other nurses qualify as counselors under this part of Maine law and every abortion clinic in the state has a counselor who can fulfill this requirement.

Every state with a parental involvement requirement has an exception for medical emergencies—except for Maryland, but the provider may waive the requirement for notification when it is not in the minor’s best interest. In many states, clinicians must notify the parents after the abortion is provided on an emergency basis. Some states have other exceptions to the parental involvement requirements, such as for cases where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest and in cases of abuse. However, these exceptions generally require that the physician report the abuse or sexual assault to the authorities. This may dissuade some minors from disclosing abuse or assault to clinicians, as survivors of sexual assault are often reluctant to report sexual violence due to fear of retaliation.

Judicial Bypass and Waiver

In all but one state with a parental involvement requirement—Florida—minors may petition a court to allow them to receive abortion care without parental consent or notification, referred to as a “judicial bypass” or “waiver”. In all these states with parental involvement laws, the proceedings are confidential, minors filing a petition have a right to a court-assigned attorney, and most require that courts issue a final ruling in the petition within a specified timeline, usually in under a week after the filing of the petition. Yet, it is difficult for minors to navigate the process. In-person attendance is generally required of minors seeking a judicial bypass/waiver. Some states require minors to attend a counseling appointment as part of the process, which may conflict with school hours making it difficult for the minor to attend. In some states, parents can be notified if the minor’s request is denied.

Additionally, the process for judicial bypass or waiver can delay timely receipt of abortion care for some minors. In a study of minors accessing care in Massachusetts, a state that requires parental consent for abortions, those who obtained parental consent accessed abortion care an average of 8.6 days after they initially contacted an abortion provider, nearly 6 days faster than those using a judicial bypass (average of 14.2 days).

Future of Consent Laws

In the past few years, policy and judicial developments have limited minors’ ability to consent to their care and access abortion and contraception services in several states. In 2023, Idaho lawmakers passed a law that criminalizes aiding a minor in obtaining an abortion outside of the state without parental consent, even if the abortion was procured in a state where abortion is legal and there are no parental involvement requirements. Tennessee lawmakers passed a similar law in 2024. Advocates for abortion rights argue these laws effectively criminalize a broad range of actions, from driving a minor across state lines to receiving an abortion, providing funds for abortion care, or even providing minors with access to information about abortion in other states where it is legal.

Both laws were challenged in federal court, where judges granted preliminary injunctions blocking their enforcement while litigation proceeded. However, in December 2024, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals allowed most of the Idaho law to go back into effect, only blocking the provisions that would have prohibited providing minors with accurate information about abortion care. In the Tennessee case, an appeal to the preliminary injunction blocking enforcement of the law is pending with the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

In 2024, lawmakers in Tennessee and Idaho also passed comprehensive legislation giving parents exclusive rights to consent to their children’s medical care and to access their medical records. Tennessee’s law contains an exception, allowing minors to retain the ability to consent to health care if it is already outlined in a separate statute. Under a separate already-existing state statute, minors had the ability to consent to birth control. Following enactment of the Tennessee law in July 2024, state public clinics stopped offering birth control to minors without parental consent, despite the law’s exception. However, after receiving clarification the exception was applicable as applied to minor’s ability to consent to birth control, clinics resumed providing these services in September 2024.

Additionally, in May 2025, a Florida state court of appeals held that the state’s judicial bypass process violates parents’ rights to raise their children under the U.S. Constitution. As discussed earlier, the judicial bypass process has been critical for teens seeking abortions in states with parental consent requirements. The case is now pending at the Florida Supreme Court. However, because the court of appeals ruling held that the process violates a U.S. constitutional right, not a state constitutional right, the case may ultimately make it to the U.S. Supreme Court with implications for minor access to abortion in Florida and beyond.

Publisher: Source link