Hospitals account for 30% of total health care spending—$1.4 trillion in 2022—with expenditures projected to rise rapidly through 2032, contributing to higher costs for families, employers, Medicare, Medicaid, and other public payers. Policymakers have sought to reduce spending on hospital care as part of a broader effort to make health care more affordable and reduce the federal deficit. In recent years, for example, there has been bipartisan interest in site-neutral payment reforms, which would reduce Medicare program and beneficiary spending by aligning Medicare rates for certain outpatient services across care settings. The next Trump administration and Republicans in Congress may also seek to cut Medicaid spending, which could result in fewer dollars flowing to hospitals.

At the same time, there are ongoing questions about the effects of policies that reduce spending on hospital finances and access to care, with particular attention to the implications for rural and safety-net hospitals. For example, Senators Cassidy and Hassan recently released a framework for site-neutral payment reforms that would reinvest savings into rural and high-needs hospitals.

This analysis examines hospital margins for non-federal general short-term hospitals in the U.S from 2018 through 2023, the most recent year with virtually complete cost report data. The analysis is based on RAND Hospital Data, a cleaned version of Medicare cost reports. Total margins are defined as net income (revenues minus expenses) divided by revenues. This analysis focuses on operating margins (instead of total margins) to examine the extent to which hospitals profited or lost money on patient care and other operating activities, rather than on other sources, such as investments. Operating margins are approximated using the same calculation as for total margins after subtracting reported investment income and charitable contributions from revenues. Results for groups of hospitals reflect aggregate margins based on total relevant revenues and expenses, which is equivalent to the average margin after weighting hospitals by their revenue. A number of datasets provide information about hospital finances, though each has limitations, and cost reports are no exception. See Methods for additional information.

Key Takeaways

- Aggregate hospital margins rebounded in 2023 following a large decrease in 2022. This is true for operating margins, which decreased from 8.9% in 2021 to 2.7% in 2022 before increasing to 5.2% in 2023. It is also true for total margins, which decreased from 10.8% in 2021 to 2.3% in 2022 before increasing to 6.4% in 2023. However, both aggregate operating margins and total margins remained below 2019 pre-pandemic levels in 2023.

- Aggregate operating margins were positive in 2023 (5.2%), but about two in five hospitals (39%) had negative margins in that year. About one in five (22%) had operating margins less than -5%.

- Operating margins were higher than average among for-profit hospitals, hospitals with a high share of commercial discharges, and system-affiliated hospitals in 2023. For-profit hospitals had higher operating margins than nonprofit and government hospitals (14.0% versus 4.4% and 3.4%, respectively). Hospitals with a relatively high commercial share of total discharges had higher operating margins than hospitals with low shares (7.5% versus 3.3% among the top versus bottom quarter based on commercial share, respectively) (quartiles are weighted by revenues throughout). System-affiliated hospitals had higher operating margins than independent hospitals (5.8% versus 2.5%).

- Operating margins in 2023 were also higher than average among hospitals with relatively high commercial prices. Operating margins were relatively high among hospitals with commercial prices that were greater than 300% of Medicare rates, especially among hospitals with high commercial shares. In contrast, operating margins were relatively low among hospitals with high Medicaid shares (see below).

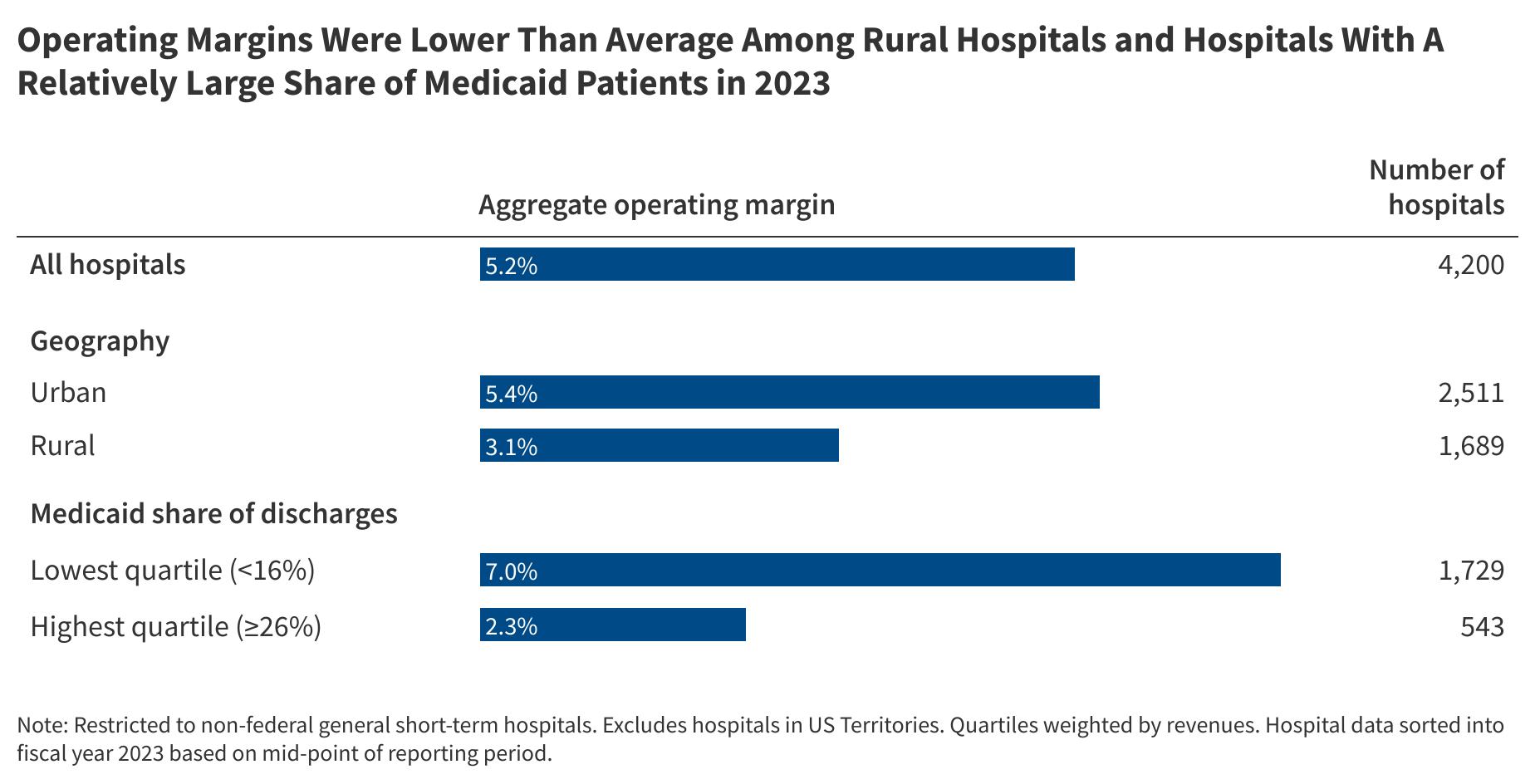

- Operating margins were lower than average among hospitals with high Medicaid shares, which was true in both rural and urban areas. Operating margins were lower among hospitals with a relatively high Medicaid share (2.3% among the top quarter of hospitals based on Medicaid shares versus 7.0% among the bottom quarter). Operating margins were relatively low for hospitals with high Medicaid shares in both rural and urban areas (1.7% and 2.3%, respectively).

- Operating margins were lower than average among rural hospitals in 2023. Operating margins were lower among hospitals in rural than urban areas (3.1% versus 5.4%, respectively) and were especially low among hospitals in rural areas that were not micropolitan areas (1.8%), i.e., that did not include and were not closely connected to any substantial population nucleus. However, operating margins were higher among for-profit than nonprofit rural hospitals (8.5% versus 3.5%, respectively). Operating margins were also lower among hospitals with Medicare rural designations, particularly among low-volume hospitals and Medicare dependent hospitals (1.7% and 1.8%, respectively).

Aggregate Hospital Margins Rebounded in 2023 Following a Large Decrease in 2022

Aggregate operating margins decreased from 8.9% in 2021 to 2.7% in 2022 before increasing to 5.2% in 2023 (Figure 1). Similarly, aggregate total margins decreased from 10.8% in 2021 to 2.3% in 2022 before increasing to 6.4% in 2023. While operating and total margins both increased in 2023, they remained below 2019 pre-pandemic levels (6.5% for operating margins and 7.6% for total margins). Operating margins were at a record high in 2021 for hospitals reimbursed under the inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) but were lower in 2022 than they had been since 2008—i.e., during the Great Recession—according to related analyses from the Medicare Payment and Advisory Commission.

Decreases in operating margins in 2022 were likely due to the erosion of COVID funds, costs associated with labor shortages, and increased supply expenses due to high inflation rates, among other factors. Improvements in 2023 may have been due a number of factors, including stabilizing labor expenses, decreases in average length of stay, and increases in revenue.

Some of the major credit rating agencies have reported relatively stable operating margins among rated not-for-profit health systems from 2022 to 2023 and have projected gradual improvements over time. These trends may differ from the main analysis here because, among other factors, they look at not-for-profit systems and report median (rather than aggregate or weighted average) operating margins. Industry reports, based on a non-representative sample of hospitals, indicate that finances have improved through October 2024 relative to 2022.

Aggregate Operating Margins Were Positive in 2023, But About Two in Five Hospitals (39%) Had Negative Margins

While aggregate operating margins were positive in 2023 (5.2%), operating margins varied substantially across hospitals. On one end of the spectrum, about one in seven hospitals (15%) had relatively high operating margins of at least 15%, while about one in five (22%) had positive but relatively modest margins of less than 5%, including about one in ten (11%) with positive margins of less than 2.5% (not shown). Having positive but modest margins may signal financial challenges for hospitals.

At the same time, about two in five hospitals (39%) had negative margins, and about one in five (22%) had margins of less than -5%. While some of these hospitals may be able to weather financial challenges for a period of time if they have sufficient days of cash on hand, those without sufficient days of cash on hand could be especially challenged to maintain current services or remain open. Based on a prior KFF analysis, the majority of nonprofit hospitals and health systems analyzed with negative operating margins had at least “strong” levels of days cash on hand in 2022, though that analysis was based on data that underrepresent entities likely to be more financially vulnerable.

Operating Margins Were Higher Than Average Among For-Profit Hospitals, Hospitals With High Commercial Discharge Shares, and System-Affiliated Hospitals and Were Lower Than Average Among Hospitals With Low Market Shares in 2023

For-profit hospitals—which accounted for 17% of facilities—had much higher operating margins than nonprofit and government hospitals (14.0% versus 4.4% and 3.4%, respectively) (see Figure 3). For-profit hospitals may have a greater motivation to operate more efficiently and engage in other strategic behaviors to increase their margins, such as focusing on relatively profitable services lines, dropping unprofitable service lines (like obstetrics), or locating in wealthier areas that have more residents with commercial insurance and fewer with public or no insurance. As is the case throughout this analysis, differences in operating margins across groups of hospitals could reflect a variety of factors.

Operating margins were also higher than average among hospitals where commercially-insured patients accounted for a relatively large share of discharges. For example, operating margins were 7.5% versus 3.3% when comparing hospitals in the top versus bottom quarter based on commercial shares (quartiles are weighted by revenues throughout). One factor that likely plays a role in these results is that commercial payers generally reimburse hospital care at higher rates than Medicare and Medicaid, the two other major payers. For instance, a KFF review found that commercial prices were nearly double Medicare rates for hospital services when averaging findings across studies, and one recent analysis found that commercial prices were 254% of Medicare rates for hospital services on average in 2022.

Operating margins were also higher among hospitals affiliated with a health system than independent hospitals (5.8% versus 2.5%). Higher operating margins among system-affiliated hospitals could reflect the effects of consolidation, among other factors. Consolidation might lead to higher margins, for example, to the extent that merging providers are able to reduce operating costs or—as suggested by a large body of evidence—charge higher prices by having greater market power.

Finally, operating margins were lower among hospitals that accounted for a relatively low share of hospital discharges in their market. For example, operating margins were 2.0% versus 7.3% when comparing the bottom versus top quarter of hospitals based on their market share (or the market share of the health system that they are a member of, as applicable). Hospitals with large market shares may be able to negotiate higher rates and, if part of a larger system, benefit from economies of scale, among other factors that could drive higher margins.

Operating Margins in 2023 Were Higher Than Average Among Hospitals With High Prices, Especially Among Those With a Relatively High Commercial Shares

Operating margins were relatively high among hospitals with commercial prices that were greater than 300% of Medicare rates (8.9%) and were even higher (10.5%) among those with a relatively high commercial share of total discharges (i.e., with at least a 25% commercial share) (see Figure 4). In contrast, operating margins were relatively low among hospitals with commercial prices below 200% of Medicare rates (1.0%) and were even lower (0.8%) among those with low commercial patient shares. This aligns with an analysis from researchers at the Urban Institute and Harvard that found that high commercial prices were associated with higher operating margins and more days of cash on hand.

Policymakers have explored a number of options to rein in commercial prices. This analysis suggests that hospitals with the highest prices and largest commercial shares as a group are in a better position to absorb any restraints on prices, though the impact would vary across hospitals.

While Operating Margins Were Higher Than Average Among Hospitals With High Commercial Shares in 2023, They Were Lower Than Average Among Hospitals With High Medicaid Shares, Which Was True in Both Urban and Rural Areas

Hospitals with high commercial shares had relatively high operating margins (e.g., 7.5% versus 3.3% when comparing the top versus bottom quarter of hospitals weighted by revenues based on commercial share) (see Figure 3 above) while hospitals with high Medicaid shares had relatively low operating margins (e.g., 2.3% versus 7.0% when comparing the top versus bottom quarter of hospitals weighted by revenues based on Medicaid share) (see Figure 5).

Operating margins in 2023 were relatively low among hospitals with high Medicaid shares in both rural and urban areas (1.7% and 2.3%, respectively) (see Figure 5). In comparison, the operating margin among all hospitals was 5.2% in 2023. While operating margins were lower among hospitals in rural than urban areas overall (3.1% versus 5.4%, respectively) (see Figure 7 below), hospitals with high Medicaid shares in urban areas stand out as another example of hospitals that were struggling more than others.

Some policymakers are especially attentive to the financial stability of safety-net hospitals given their role in providing access to patients with limited resources and other sources of vulnerability. The share of patients covered by Medicaid may signal the extent to which a given hospital cares for a disproportionate share of low-income patients (see Methods for more detail).

Operating Margins Were Also Lower Than Average Among Hospitals With High Medicare Shares in 2023

Operating margins were 4.3% in 2023 among hospitals in the top quarter based on Medicare share of discharges compared to 5.8% among hospitals in the bottom quarter (see Figure 6). Part of this difference may reflect the fact that hospitals with high Medicare shares were more likely to be in rural areas (54% of hospitals in the top quarter of Medicare shares were in rural areas versus 23% of the hospitals in the bottom quarter). As described below, rural hospitals had lower than average operating margins in 2023.

While operating margins among hospitals in the top quarter of Medicare shares were lower than among hospitals overall, they were higher relative to hospitals in the top quarter of Medicaid shares (4.3% versus 2.3%, respectively).

Operating Margins Were Lower Than Average Among Rural Hospitals in 2023

Operating margins were lower among hospitals in rural versus urban (nonmetropolitan versus metropolitan) areas (3.1% versus 5.4%, respectively) and were especially low among hospitals in rural areas that were not micropolitan areas (1.8%) (Figure 7), i.e., that did not include and were not closely connected to any substantial population nucleus (see Methods for more about urban and rural definitions). While 48 states in this analysis had at least one rural hospital, rural hospitals were distributed unevenly across the country. For example, a quarter of rural hospitals were located in Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, or Texas. Rural hospitals often face unique financial challenges, such as low patient volume, which may lead to higher costs on average and limit the ability to offer specialized services.

Operating margins varied across rural hospitals in 2023, as was the case when looking at hospitals overall. For example, more than four in ten (44%) rural hospitals had negative operating margins while more than half (56%) had positive operating margins, including one in ten (10%) with operating margins of at least 15%. Operating margins were higher among rural for-profit than rural non-profit hospitals (8.5% versus 3.5%) and lower (0.3%) among rural government hospitals. Operating margins were also higher among system-affiliated versus independent rural hospitals (4.8% versus 0.6%, respectively).

Operating margins were lower among hospitals with Medicare rural designations than other hospitals. Low-volume hospitals (hospitals with few discharges that are a minimum distance from other facilities) and Medicare dependent hospitals (small rural hospitals with high Medicare inpatient shares) had the lowest operating margins (1.7% and 1.8%, respectively) (Figure 7). Operating margins were also lower on average among critical access hospitals (rural hospitals with at most 25 beds that with some exceptions are a minimum distance from other facilities) and sole community hospitals (hospitals that are the only source of short-term, acute inpatient care in a region) relative to hospitals without a Medicare rural designation (4.1% and 4.2%, respectively, versus 5.7%). About half of low-volume, Medicare dependent and sole community hospitals had negative operating margins in 2023 (52%, 52%, and 49%, respectively), as did 40% of critical access hospitals. A smaller share (35%) of hospitals without a Medicare rural designation had negative operating margins.

Senators Cassidy and Hassan recently released a framework for site-neutral payment reforms that some of the savings be reinvested into sole community, low-volume, and Medicare dependent hospitals. As noted above, each of these groups had lower operating margins than did hospitals without a rural designation. The framework does not mention new funds for critical access hospitals, which would likely be exempt from site-neutral payment reforms.

Policymakers have had ongoing concerns about the financial health of rural hospitals and the implications for access to care and the local economy. At the same time, it may be difficult to sustain some rural hospitals—such as those in areas with shrinking populations—and some have argued that care in at least some scenarios should be moved towards other settings, including telehealth, outpatient facilities, and larger regional hospitals.

Operating Margins Were Higher Than Average Among Hospitals With a Large Number of Beds and Among Minor Teaching Hospitals in 2023

Hospitals with greater than 500 beds had higher operating margins (6.3%) than those with fewer beds (e.g., 3.9% among hospitals with 51 to 100 beds) (see Figure 8). Minor teaching hospitals had higher margins (6.2%) than major teaching (4.3%) and non-teaching (5.1%) hospitals. Minor teaching hospitals are defined as facilities with interns or residents but at most one full-time equivalent intern or resident for every four beds, and major teaching hospitals are defined as facilities with more.

Operating Margins Varied Across States in 2023

Aggregate operating margins were at least 10% in five states (Alaska, Florida, Texas, Utah, and Virginia) but negative in four states (Michigan, New Mexico, Washington, and Wyoming) (see Figure 9). Differences likely reflect a variety of unique state circumstances, such as demographics, hospital ownership and cost structure, commercial reimbursement rates, and state and local health and tax policy. For instance, operating margins may have been high in Texas in part because the state has a relatively large number of for-profit hospitals (which have higher operating margins on average), among other factors. The same is true of Florida, which may have also had high operating margins in part due to the relatively high commercial prices in the state. As an example of a state on the other end of the spectrum, margins may have been relatively low in Wyoming in part because the vast majority of hospitals are in rural areas (92% compared to 40% of all hospitals), among other factors. It is also possible that a small number of hospitals with large revenue could have a large impact on aggregate operating margins, especially in states with relatively few hospitals, like Alaska.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Publisher: Source link