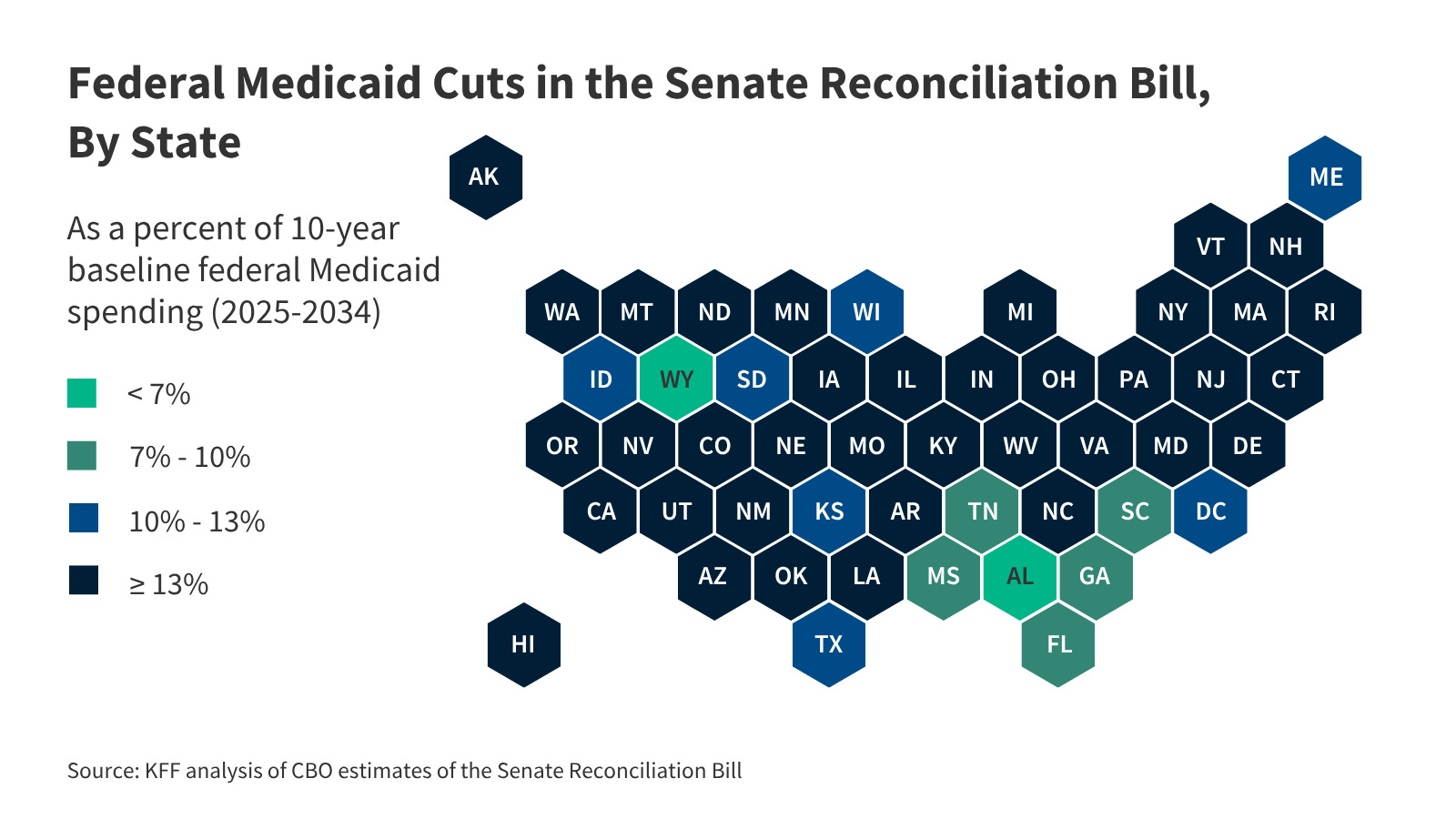

The Senate passed their version of the reconciliation bill on July 1, which differs from the version that passed the House on May 22. The Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) latest cost estimate, which corresponds to the Senate Budget Committee’s version of the bill, shows that the bill would reduce federal Medicaid spending by $1 trillion and increase the number of uninsured people by 11.8 million. Building on prior KFF analysis of the House-passed reconciliation bill, this analysis allocates CBO’s federal spending reductions in the Senate reconciliation bill across the states. The Medicaid reconciliation provisions are numerous and complicated, but the majority of federal savings stem from work requirements for the expansion group, limiting states’ ability to raise the state share of Medicaid revenues through provider taxes, increasing barriers to enrolling in and renewing Medicaid coverage, and restricting state-directed payments to hospitals, nursing facilities, and other providers.

This analysis allocates the CBO’s estimated reduction in federal spending across states based on KFF’s state-level data and where possible, prior modeling work; and shows the federal spending reductions relative to KFF’s projections of federal spending by state under current law. KFF allocates the spending reductions provision-by-provision, pulling in a variety of data sources on which states are estimated to be most affected by each provision (see Methods). CBO has not yet provided estimates of the Senate-passed reconciliation bill, so KFF adjusted the prior CBO estimates by removing CBO’s estimated spending reductions for the three sections that were removed from the Senate Budget Committee bill by an amendment, which included a federal match rate penalty for states that have expanded coverage for immigrants, a prohibition on gender affirming care, and increased federal matching funds for Alaska and Hawaii. KFF did not include the $50 billion in funding for state grants through a Rural Health Transformation Program in the Senate-passed bill and did not account for other changes to the legislative language that were more complicated, including: appropriating new implementation funding for several provisions, retaining some elements of Biden-era regulations that had already taken effect, and applying new restrictions on provider taxes to local government taxes in expansion states.

CBO has not published updated estimates of the number of people who would lose Medicaid under the Senate’s reconciliation bill, so this analysis does not include updated enrollment estimates like those included in KFF’s analysis of the House-passed reconciliation bill. CBO’s most recent estimate of Medicaid enrollment loss from an earlier version of the House reconciliation bill was 10.3 million people in 2034, which was associated with a $625 billion decrease in Medicaid spending (reflecting preliminary estimates prepared for the House Committee on Energy and Commerce). Given the Medicaid spending reductions are considerably larger, more than 10.3 million people are likely to lose Medicaid from the Senate bill.

This analysis does not predict how states will respond to federal policy changes, and anticipating how states will respond to Medicaid changes is a major source of uncertainty in CBO’s cost estimates. Instead of making state-by-state predictions, CBO generates a national figure by estimating the percent of the affected population that lives in states with different anticipated types of policy responses. For example, different states might choose to implement a work requirement with reporting requirements that are easier or harder to comply with. In estimating the costs of the legislation, CBO assumes that in aggregate, states would replace half of reduced federal funds with their own resources in response to provisions that reduce the resources available to states, such as limits on provider taxes. For provisions that reduce enrollment but don’t affect the division of costs between the federal and state governments, such as work requirements, CBO estimates that the federal and state Medicaid spending would go down. However, those assumptions reflect states’ responses as a whole and are likely to vary and may not apply in all states.

To the extent that states’ responses are far different from the overall average response, changes in federal Medicaid spending will be larger or smaller than what is shown here. States could make further Medicaid cuts, which would result in spending reductions greater than is estimated here and further reduce states’ Medicaid spending. Alternatively, states could increase their spending on Medicaid to mitigate the effects of federal cuts, which could result in spending reductions that are smaller than is estimated here. This analysis illustrates the potential variation by showing a range of spending effects in each state, varying by plus or minus 25% from the CBO estimated midpoint.

Key Take-Aways

- KFF estimates that the Senate reconciliation bill would reduce federal Medicaid spending by $1 trillion.

- The five biggest sources of Medicaid savings in the Senate reconciliation bill sum to $896 billion in savings, which is 87% of the total, and include:

- Mandating that adults who are eligible for Medicaid through the ACA expansion meet work and reporting requirements ($326 billion),

- Repealing the Biden Administration’s rule simplifying Medicaid eligibility and renewal processes ($167 billion),

- Establishing a moratorium on new or increased provider taxes and reducing existing provider taxes in expansion states ($191 billion),

- Revising the payment limit for state directed payments ($149 billion), and

- Increasing the frequency of eligibility redeterminations for the ACA expansion group ($63 billion).

- Provisions that would only apply to states that have adopted the ACA expansion account for $526 billion, just over half of the total amount of federal spending reductions.

- Federal cuts to states of $1 trillion over 10 years would represent 15% of federal spending on Medicaid over the period (this is up from 12% in the House-passed reconciliation bill). The spending cuts vary by state; Louisiana and Virginia are the most heavily affected with spending cuts of 21% over the period.

Methods |

| Data: This analysis uses the latest data available from various data sources to illustrate the potential impact of a $1 trillion cut to federal Medicaid spending across states. Data sources include:

Estimating Total Federal Funding Reductions: CBO’s cost estimate provided the reduction in federal outlays for Medicaid provisions, which summed to $1 trillion. This analysis does not include any interactions and assumes interactions are related to the Health Tax section (not Medicaid) based details included in a second CBO score estimated relative to a current policy baseline. This analysis does not include the $50 billion in funding in the Senate-passed bill for state grants through a Rural Health Transformation Program and removed CBO’s estimated spending reductions for three sections that were removed from Senate Budget Committee bill by an amendment. This included the federal match rate penalty for states that have expanded coverage for immigrants (Sec. 71110), the prohibition on gender affirming care (Sec. 71114), and increased federal matching funds for Alaska and Hawaii (Sec. 71124). Allocating Federal Funding Reductions Across States: This analysis allocates the ten-year federal Medicaid cut across states as follows:

For all estimates, the federal share of spending in FY 2024 is estimated using a 90% match rate for the ACA expansion group and the FY 2024 traditional federal match rates plus a 1.5 percentage point increase for the first quarter of FY 2024 (accounting for the final phase out quarter of the pandemic-era enhanced federal match rate) for the remaining eligibility groups. Limitations: This analysis allocates the CBO’s estimated reduction in federal spending across states based on KFF’s state-level data and where possible, prior modeling work. The most significant limitations of this approach are as follows.

|

Publisher: Source link