Summary

Stark racial disparities in maternal and infant health in the U.S. have persisted for decades despite continued advancements in medical care. Compared to other high-income countries, the U.S. remains the country with the highest rate of maternal deaths. The disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people of color brought increased attention to health disparities, including the longstanding inequities in maternal and infant health. Subsequently, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, growing barriers to abortion, cuts to staff and programs within the U.S Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the passage of the 2025 tax and budget law all have the potential to further widen existing disparities in maternal health.

This brief provides an overview of racial disparities for selected measures of maternal and infant health, discusses the factors that drive these disparities, and provides an overview of policy changes that may impact them. It is based on KFF analysis of publicly available data from CDC WONDER online database, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Vital Statistics Reports, and the CDC Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System.

While this brief focuses on racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and infant health, wide disparities also exist across other dimensions, including income, education, age, and other characteristics. For example, there is significant variation in some of these measures across states and disparities between rural and urban communities. Data and research often assume cisgender identities and may not systematically account for people who are transgender and non-binary. In some cases, the data cited in this brief use cisgender labels to align with how measures have been defined in underlying data sources. Key takeaways include:

Large racial disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes persist. Pregnancy-related mortality rates among Black women are over three times higher than the rate for White women (49.4 vs. 14.9 per 100,000). Black, American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHPI) women also have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women. Infants born to Black, AIAN, and NHPI people have markedly higher mortality rates than those born to White people.

Maternal and infant health disparities reflect broader underlying social and economic inequities that are rooted in racism and discrimination. Differences in health insurance coverage and access to care play a role in driving worse maternal and infant health outcomes for people of color. However, inequities in broader social and economic factors, including income, are primary drivers for maternal and infant health disparities. Moreover, the persistence of disparities in maternal health across income and education levels, points to the importance of addressing the roles of racism and discrimination as part of efforts to improve health and advance equity.

Recent actions by the Trump administration and Congress reflect a shift away from prioritizing maternal and infant health equity and may contribute to widening disparities. Several key programs that historically supported expanding access to care and services and efforts to address racial disparities, such as diversifying the health care workforce and enhancing data collection and reporting, now face funding cuts or elimination. Other recent federal program and budget cutbacks, including the reduction or elimination of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, may undermine efforts to improve disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes. Moreover, the 2025 tax and budget law is anticipated to lead to large coverage losses, particularly in Medicaid, which is a primary source of care for people of color. Coverage losses will likely contribute to access barriers, including for maternal care. Additionally, state variation in access to abortion in the wake of the overturning of Roe v. Wade may exacerbate existing racial disparities in maternal health.

Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health

Pregnancy-Related Mortality Rates

In 2023, approximately 676 women died in the U.S. from causes related to or worsened by pregnancy. This is a decrease from 793 maternal deaths in 2022. Pregnancy-related deaths are deaths that occur within one year of pregnancy. The pregnancy-related mortality rate decreased among White and Hispanic women, will there were no significant changes for Asian or Black women. Approximately one in five (20%) deaths occur during pregnancy, nearly one quarter (23%) occur during labor or within the first week postpartum, and more than half (57%) occur one week to one year postpartum, underscoring the importance of access to health care beyond the period of pregnancy. Recent data show that more than eight out of ten (87%) pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.

As of 2023, Black people are more than three times as likely as White people to experience a pregnancy-related death (49.4 vs. 14.9 per 100,000 live births) in 2023 (Figure 1). The rate for Hispanic and Asian people is lower compared to that of White people (12.3 and 10.7 vs. 14.9 deaths per 100,000 live births). Data from 2023 were insufficient to identify mortality among AIAN and NHPI women. However, earlier data from 2021 show that AIAN and NHPI people (118.7 and 111.7 per 100,000, respectively) had the highest rates of pregnancy-related mortality across racial and ethnic groups.

Research shows that this disparity for Black women increases by age and persists across education and income levels. Data show higher pregnancy-related mortality rates among Black women who completed college education than among White women with the same educational attainment and White women with less than a high school diploma. Other research also shows that Black women are at significantly higher risk for severe maternal morbidity, including conditions such as preeclampsia, which is significantly more common than maternal death. Further, AIAN, Black, NHPI, Asian, and Hispanic women have higher rates of admission to the intensive care unit during delivery compared to White women, which is considered a marker for severe maternal morbidity.

Birth Risks and Outcomes

Black, AIAN, and NHPI women are more likely than White women to have certain birth risk factors that contribute to infant mortality and can have long-term consequences for the physical and cognitive health of children. Preterm birth (birth before 37 weeks gestation) and low birthweight (defined as a baby born less than 5.5 pounds) are some of the leading causes for infant mortality. Receiving pregnancy-related care late in a pregnancy (defined as starting in the third trimester) or not receiving any pregnancy-related care at all can also increase the risk of pregnancy complications. Black, AIAN, and NHPI women have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women (Figure 2). Notably, NHPI women are four times more likely than White women to begin receiving prenatal care in the third trimester or to receive no prenatal care at all (22.4% vs. 4.7%). Black women also are nearly twice as likely compared to White women to have a birth with late or no prenatal care compared to White women (10.4% vs. 4.7%).

While teen birth rates overall have declined over time, they are higher among Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHPI teens compared to their White counterparts (Figure 3). In contrast, the birth rate among Asian teens is lower than the rate for White teens. Many teen pregnancies are unplanned, and pregnant teens may be less likely to receive early and regular prenatal care. Teen pregnancy also is associated with increased risk of complications during pregnancy and delivery, including preterm birth. Teen pregnancy and childbirth can also have social and economic impacts on teen parents and their children, including disrupting educational completion for the parents and lower school achievement for the children. Research studies have found that increased use of contraception as well declines in teen sexual activity have helped lower the rate of teen births nationally.

Reflecting these increased risk factors, infants born to AIAN, Hispanic, Black, and NHPI women are at higher risk for mortality compared to those born to White women. Infant mortality is defined as the death of an infant within the first year of life, but most cases occur within the first month after birth. The primary causes of infant mortality are birth defects, preterm birth and low birthweight, sudden infant death syndrome, injuries, and maternal pregnancy complications. Infant mortality rates have declined over time, although the 2023 rate is unchanged from the 2022 rate (5.6 per 1,000 births, respectively). However, disparities in infant mortality have persisted and sometimes widened for over a century, particularly between Black and White infants. As of 2023, infants born to Black women are over twice as likely to die relative to those born to White women (10.9 vs. 4.5 per 1,000), and the mortality rate for infants born to AIAN and NHPI women (9.2 and 8.2 per 1,000) is nearly twice as high (Figure 4). The mortality rate for infants born to Hispanic mothers is similar to the rate for those born to White women (5.0 vs. 4.5 per 1,000), while infants born to Asian women have a lower mortality rate (3.4 per 1,000).

Data also show that fetal death or stillbirths—that is, pregnancy loss after 20-week gestation—are more common among NHPI, Black and AIAN women compared to White and Hispanic women. Moreover, causes of stillbirth vary by race and ethnicity, with higher rates of stillbirth attributed to diabetes and maternal complications among Black women compared to White women.

Based on the most recently available federally published estimates from 2018, about one in five AIAN, Asian or Pacific Islander, and Black women reported symptoms of pregnancy-related depression compared to about one in ten White women (Figure 5). Hispanic women (12%) had similar rates of depression during and after childbirth compared to their White counterparts (11%). A recent study among women in Southern California suggests that the prevalence of PPD) has grown over the past decade , driven by increases among Black and Asian and Pacific Islander women. Women of color experience increased barriers to mental health care and resources, along with racism, trauma and cultural barriers. Research suggests that perinatal mental health conditions are a leading underlying cause of pregnancy-related deaths and that individuals with perinatal depression are also at increased risk of chronic health complications such as hypertension and diabetes. Infants of mothers with depression are more likely to be hospitalized and die within the first year of life.

Factors Driving Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health

The factors driving disparities in maternal and infant health are complex and multifactorial. They include differences in health insurance coverage and access to care. However, broader social and economic factors and structural and systemic racism and discrimination also play a major role (Figure 7). In maternal and infant health specifically, the intersection of race, gender, poverty, and other social factors shapes individuals’ experiences and outcomes. Recently there has been broader recognition of the principles of reproductive justice, which emphasize the role that the social determinants of health and other factors play in reproductive health for communities of color. Notably, Hispanic women and infants fare similarly to their White counterparts on many measures of maternal and infant health despite experiencing increased access barriers and social and economic challenges typically associated with poorer health outcomes. Research suggests that this finding, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic or Latino health paradox, in part, stems from variation in outcomes among subgroups of Hispanic people by origin, nativity, and race, with better outcomes for some groups, particularly recent immigrants to the U.S. However, the findings still are not fully understood.

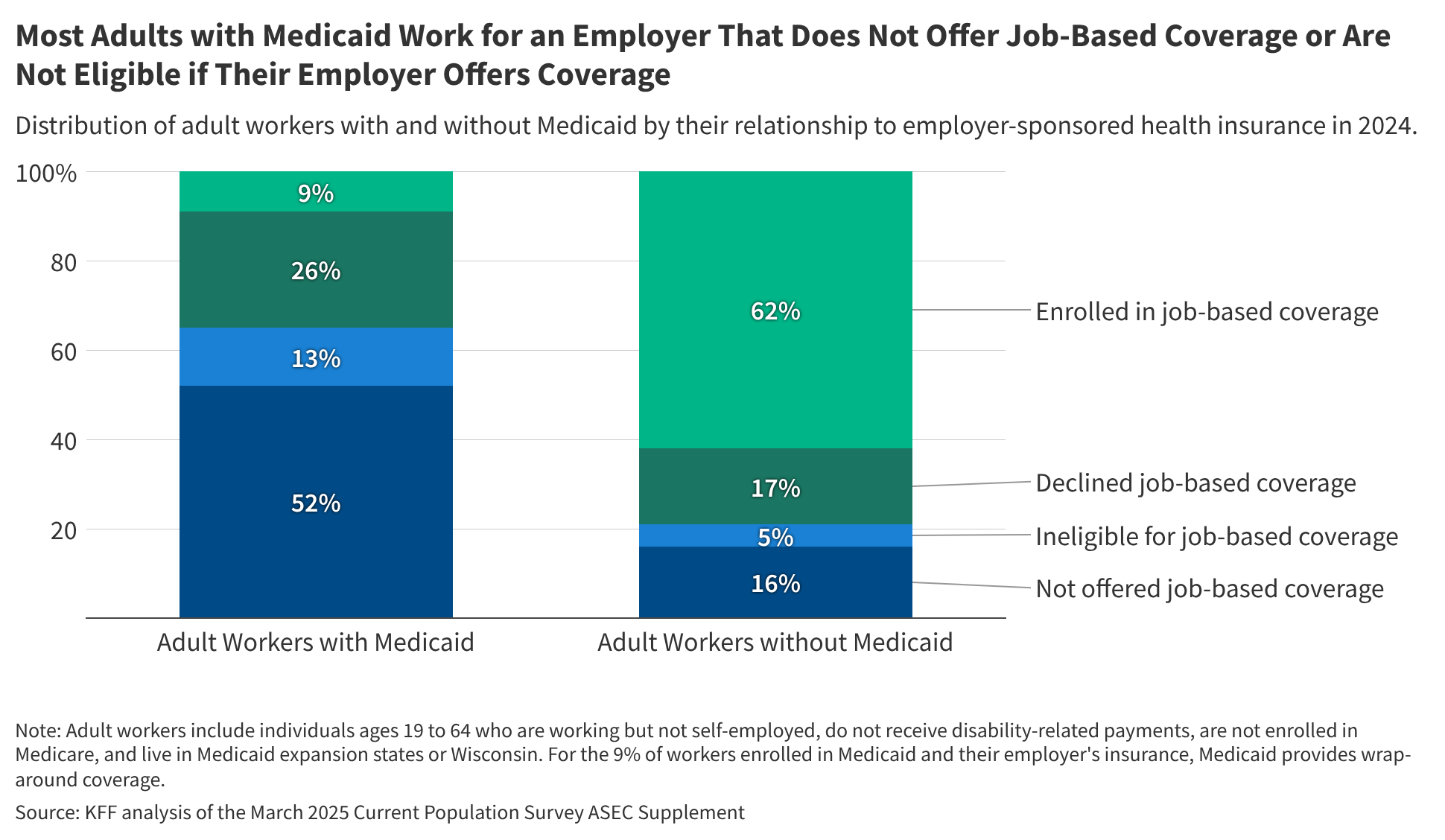

Disparities in maternal and infant health, in part, reflect increased barriers to care for people of color. Research shows that coverage before, during, and after pregnancy facilitates access to care that supports healthy pregnancies, as well as positive maternal and infant outcomes after childbirth. Overall, people of color are more likely to be uninsured and face other barriers to care. Medicaid helps to fill these coverage gaps during pregnancy and for children, covering more than two-thirds of births to women who are Black or AIAN. Given its significant role as a payor of maternity care for women of color, several health care professionals and state Medicaid programs have developed initiatives to improve maternal health and decrease maternal mortality and morbidity, such as broader inclusion of doulas as Medicaid providers. However, AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people are at increased risk of being uninsured prior to their pregnancy, which can affect access to care before pregnancy and timely entry to prenatal care. Beyond health coverage, people of color face other increased barriers to care, including limited access to providers and hospitals and lack of access to culturally and linguistically appropriate care.

Several areas of the country, particularly in the South, which is home to a large share of the Black population, have gaps in obstetrics providers. AIAN women also are more likely to live in communities with lower access to obstetric care. These challenges may be particularly pronounced in rural and medically underserved areas. For example, research suggests that the steep closures of hospitals and obstetric units over the past decade in rural areas has a disproportionate negative impact on Black infant health. Suggested approaches for stemming shortages include more training programs for perinatal nurses and midwives, raising Medicaid payment rates, and expansion of midwifery and birth centers services.

Research also highlights the role racism and discrimination play in driving racial disparities in maternal and infant health. Research has documented that social and economic factors, racism, and chronic stress contribute to poor maternal and infant health outcomes, including higher rates of pregnancy-related depression and preterm birth among Black women and higher rates of mortality among Black infants. In recent years, research and news reports have raised attention to the effects of provider discrimination during pregnancy and delivery. News reporting and maternal mortality case reviews have called attention to a number of maternal and infant deaths and near misses among women of color where providers did not or were slow to listen to patients. A recent report determined that discrimination, defined as treating someone differently based on the class, group, or category they belong to due to biases, stereotypes, and prejudices, contributed to 30% of pregnancy-related deaths in 2020. In one study, Black and Hispanic women reported the highest rates of mistreatment (such as shouting and scolding, ignoring or refusing requests for help during the course of their pregnancy). Even after controlling for insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions, people of color are less likely to receive routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of care. Another study found that Black women are more likely to receive a cesarian section compared to White women while controlling for health status, suggesting that differences in provider judgement and structural inequalities may be contributing to the disparity. A 2023 KFF survey found that about one in five (21%) Black women say they have been treated unfairly by a health care provider or staff because of their racial or ethnic background. A similar share (22%) of Black women who have been pregnant or gave birth in the past ten years say they were refused pain medication they thought they needed.

Current Policies Impacting Maternal and Infant Health Disparities

Since President Trump took office in January 2025, the Administration and Congress have made significant health policy changes. While in some cases pregnant and postpartum people have been specifically exempted or protected from changes, many changes may have significant impacts on maternal and infant health that could exacerbate existing disparities.

President Trump’s executive orders rolling back federal diversity efforts could exacerbate longstanding disparities in maternal health. As one of his first actions in office, President Trump signed executive orders revoking federal DEI related programs and actions in the federal government and among federal contractors and grantees. In implementing President Trump’s executive orders, the administration has taken significantly broader actions beyond eliminating DEI programs to include eliminating priorities, actions, information, data, and funding related to concepts of diversity or disparities among federal agencies as well as federal contractors and grantees. The broad nature of these actions risks reversing progress on health equity and may lead to widening disparities in maternal health.

Recent federal restructuring may reverse progress on maternal and infant health, particularly for communities already facing persistent disparities. On March 27, 2025, the Trump administration announced an Executive Order reorganizing HHS, which has disrupted key programs affecting maternal health. This impacts included laying off most staff in the CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health, halting community-based maternal health grants, erasing the prior White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis, and closing several federal offices that supported state and local efforts to address racial disparities in maternal care. The restructuring has also eliminated key initiatives, including the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), which for decades provided data to track maternal experiences and inform evidence-based policies, and the Safe to Sleep Campaign, a national effort to reduce sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). These rollbacks come at a time when sleep-related infant deaths have risen nearly 12% between 2020 and 2022, with SIDS among Black infants increasing by 15% in 2020.

The 2025 tax and spending legislation makes large cutbacks in federal Medicaid spending that are expected to lead to large coverage losses, which will likely reduce access to care, including maternal care. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the law will reduce federal Medicaid spending over the next decade by an estimated $911 billion and increase the number of uninsured people by 10 million. Given the disproportionate role Medicaid plays in covering women of color, they are at increased risk for being affected by program cutbacks. In 2023, Medicaid covered 37% of AIAN 30% of Black and 26% of Hispanic reproductive age women, compared to 20% of reproductive age women overall. Moreover, among women of reproductive age enrolled in Medicaid, nearly four in ten are covered through the Medicaid expansion and could be at risk of losing coverage due to new work and eligibility requirements under the law. While the law provides exemptions from new work requirements for pregnant and postpartum women and for adults with children under age 14, many may still be at risk for losing coverage if they face challenges documenting information necessary to quality for the exemption. The requirements may also limit access to coverage before pregnancy, a particularly important time for addressing preventive care and managing chronic conditions, which are associated with healthier pregnancy outcomes.

The law also imposes a one-year ban on federal Medicaid payments to certain family planning providers, including all Planned Parenthood clinics, which could weaken resources and care that support maternal and infant health. This policy prohibits some family planning clinics that also offer abortion services from receiving any Medicaid payments for contraceptive and other preventive services. Because Medicaid covers 90% of the cost of family planning services, losing this funding would be a major financial blow. While Planned Parenthood clinics represent a small share of the reproductive health safety net overall, they serve many patients of color, provide a significant portion of contraceptive care and are often the only provider in rural or underserved areas. Excluding them from Medicaid could result in clinic closures, reduced services, and fewer reproductive care options for low-income women.

In addition, President Trump’s policies and budget proposals are threatening to dismantle the Title X family planning program, disproportionately affecting communities already facing higher barriers to care. Title X, a federal program established in 1970, provides funding to clinics that offer contraceptive services, STI testing, and cancer screenings to low-income and uninsured patients. These clinics provide care to a diverse population, with nearly a quarter (23%) of the patient population identifying as Black, more than a third (36%) as Hispanic or Latino, and about a fifth (19%) reporting limited proficiency in English. In recent years, the program has faced mounting restrictions. During President Trump’s first term, his administration implemented rules that barred clinics from participating in Title X if they offered or referred for abortion services, resulting in roughly 1,000 clinics losing Title X funding. While the Biden administration later reversed these restrictions, the second Trump administration has resumed efforts to limit the program by withholding funds from some grantees and proposing to eliminate all funding for the program. If enacted, these policies would dismantle the program, leaving many rural and underserved communities with fewer resources for affordable reproductive health care.

State abortion bans and restrictions may exacerbate poor maternal and infant health outcomes and access to care. Since the Dobbs ruling in June 2022, about half of states have banned abortion or restricted it to early in pregnancy. People of color are disproportionately affected by these bans and restrictions as they are at higher risk for pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity, are more likely to obtain abortions, and more likely to face structural barriers that make it more difficult to travel out of state for an abortion. While the number of abortions has slightly increased nationally since the ruling, ongoing and impending legal challenges, state legislative efforts, and federal executive actions could further alter the reproductive care landscape and have impacts beyond abortion counts. A recent JAMA study, for instance, found that fertility rates have increased in states with complete or 6 week abortion bans, particularly among Black and Hispanic populations compared to White populations. A concurrent study showed infant mortality rates have also risen in these states and the increases were larger among Black infants. Abortion bans are exacerbating maternity workforce shortages, as some clinicians do not want to work in areas that criminalize their practice and restrict their ability to provide evidence-based care.

Publisher: Source link